|

Auto Tiler Library

|

|

|

Auto Tiler Library

|

|

The Auto-tiler is a tool that runs on users PCs before GAP8 code compilation and automatically generates GAP8 code for memory tiling and transfers between all memory levels: GAP8 has two levels in-chip memory (L1 and L2) and an external optional 3rd level (L3).

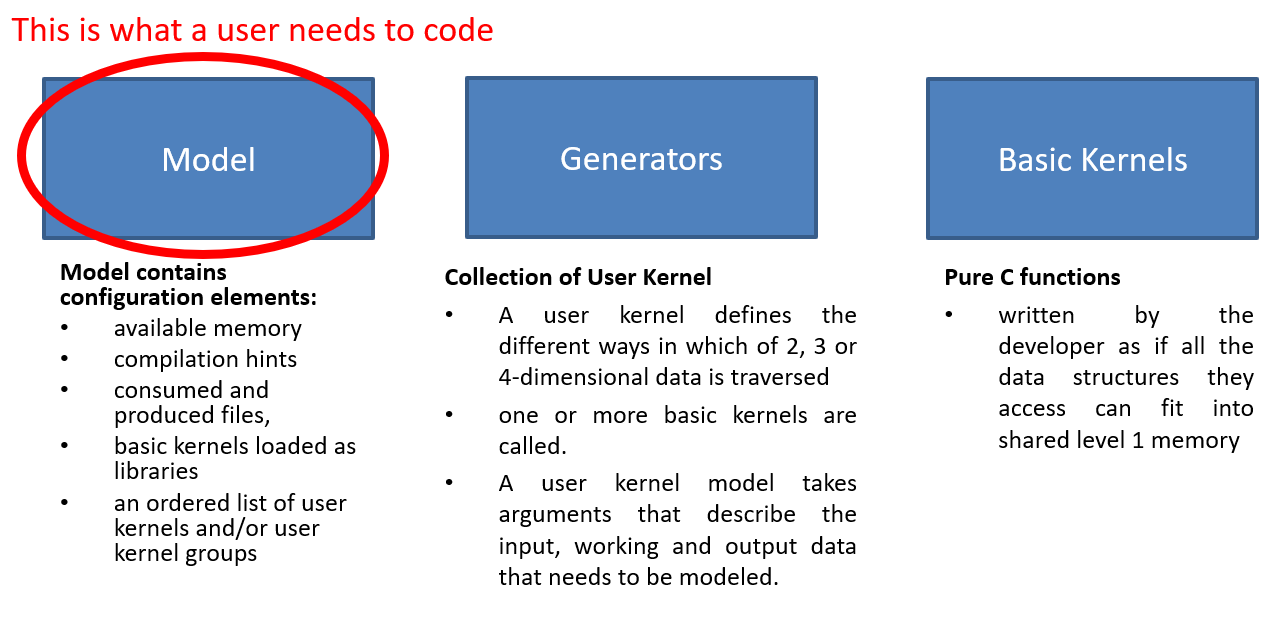

From a user perspective, the purpose of the auto-tiler is twofold:

For several of the use cases the former will be enough to build your own application.

To exploit generators provided in the sdk, all the user needs to do is to write his own model.

In the SDK we provide several examples on how to write your own model:

Here you can browse them on github.

Here is a list of generators provided within the SDK:

All the generators source code can be found here:

You can browse it here on github.

If you want to extend the generators suite that we provide in our SDK in this paragraph we explain all the auto-tiler fundamentals.

GAP8's memory hierarchy is made up of three levels:

There are two DMA units. The micro-DMA unit, responsible for transfers to and from peripherals into the level 2 memory and the cluster-DMA unit, which can be used to schedule unattended transfers between level 2 and level 1 memory.

The level 1 and level 2 memories are also directly accessible by all the cores in the chip.

To keep the size of the chip as small as possible and to reduce the amount of energy spent in memory accesses GAP8 does not use data caching. Level 3 memory is the most constrained since data must be moved into the chip level 2 memory with the micro-DMA unit (streaming).

The ideal memory model for a developer is to view memory as one large continuous area that is as big and as fast as possible. This is normally achieved by a data cache which automatically moves data between memory areas. Since GAP8 does not implement data caching and since GAP8's cluster is optimized for processing data in a linear or piece-wise linear fashion, we provide a software tool, the GAP8 auto-tiler, to help the developer by automating memory movements for programs of this type.

The auto-tiler uses defined patterns of data access to anticipate data movements ensuring that the right data is available in level 1 memory when needed. Since GAP8's cluster-DMA and micro-DMA units operate in parallel with all the GAP8 cores, the auto-tiler can use these units to make these pipelined memory transfers quasi-invisible from a performance point of view. The auto-tiler decomposes 1, 2, 3 and 4-dimensional data structures into a set of tiles (2-dimensional structures) and generates the C code necessary to move these tiles in and out of shared level 1 memory. The developer concentrates on the code that handles simple 2D tiles and the auto-tiler takes care of moving tiles into and out of level 1 memory as necessary and calling the developer's code.

Below is a list of the entities that make up the configuration or data model necessary for the GAP8 auto-tiler to generate functioning code. We refer extensively to a 'model' which is used to indicate the use of the auto-tiler API to declare the signature of developer functions (basic kernels) and define iterated assemblies of basic kernels which actually cause the auto-tiler to generate code.

User kernels User kernel models group calls to basic kernels and allow the GAP8 auto-tiler to generate a C function for that grouping. A user kernel defines the different, predefined ways in which of 2, 3 or 4-dimensional data is traversed, and one or more basic kernels are called. A user kernel model takes arguments that describe the input, working and output data that needs to be modeled.

User kernels consume and process data through these user kernel arguments. Kernel argument models describe argument location in the memory hierarchy (level 3, level 2 or level 1), direction (in, out, in out, pure buffer), inner dimension (width and height), dimensionality (1D, 2D, 3D, 4D). Kernel argument models include several other attributes that are used to constrain the tiles that are generated from the argument (preferred size, odd/even size, etc.) or to provide hints that control the double or triple-buffering strategy used in the generated code. Calls to basic kernels can be inserted in different places in the generated iterative code (inner loop, loop prologue, loop epilogue, etc.). The calls are bound to arguments which can either be from the kernel argument model described above, direct C arguments or immediates. User kernels are described in detail in the section [User kernels].

The auto-tiler model is created through a series of calls to functions from the auto-tiler library. In addition to these calls, the developer can add whatever application specific code needed. Compiling and running the model on the build system creates a set of C source files that are then compiled and run on GAP8.

The basic object on which the GAP8 auto-tiler works is a 2D space that we call a data plane. Each user kernel argument corresponds to a data plane and potentially each user kernel argument can have a different width and height. For example, if the kernel we want to write produces one output for each 2x2 input sub region the input argument will be a data plane of WxH in size and the output argument will be a data plane of size (W/2)x(H/2).

This basic data plane can then be extended to 3 or 4 dimensions. Extending the dimension of a data plane is simply a repletion of the 2-dimensional basic data plane.

The GAP8 auto-tiler splits basic data planes into tiles, the number of tiles for each user kernel argument is identical but their dimension can vary from one argument to the other.

The GAP8 auto-tiler makes the following hypothesis about the user algorithm:

Which can be rewritten as:

Not all algorithms fits into this template but we believe it captures a large family of useful algorithms.

The illustrative examples below show how an entire auto-tiler model is constructed. Don't worry if they are confusing at the start. As you read the other sections of the manual the examples should become clear.

In this example, we want to add two integer matrices and store the result in a third matrix.

You can see the full code for the example in autotiler/examples/MatrixAdd

The basic kernel that does the job of addition is MatSumPar. It takes arguments of pointers to two input tiles and one output tile, these three tiles are expected to have the same dimensions which are passed as W and H. It is expected that the 3 matrices fit into shared level 1 memory.

The basic kernel for this example is shown in the basic kernel section below.

We first model the template of basic kernel MatSumPar function call.

And then we model a user kernel generator with no restrictions on the matrices dimensions (of course they need to fit into the level 2 memory). This describes the input and output parameters of the generated function and the way that the data is iterated.

During our build process the generator code is compiled and MatAddGenerator("MatAdd", 200, 300) is called. The GAP8 auto-tiler generates the following code:

This user kernel also operates on a 2D integer matrix but returns the maximum value in this matrix. Here we model a classic parallel map/reduce algorithm to accomplish the task. We use a basic kernel, KerMatrixMax, which operates on a tile. KerMatrixMax takes as arguments: a pointer to a tile In, the dimensions of this tile (W and H), a pointer to the vector Out (a buffer whose dimension is the number of tiles) to store the max for each tile. KerMatrixMax also takes an argument CompareWithOut, which indicates if a valid maximum is already available in the output vector and should be compared against the maximum calculated in the current tile.

Each basic kernel call will return the maximum in a sub section of the full input matrix. To get the final result we have to reduce the set of sub-results into a single result. This is our second kernel: KerMatrixMaxReduction. As a first argument In it takes the vector of maximums produced by the first basic kernel as well as its dimension Ntile. It produces a pointer to a single maximum in Out (a 1 x 1 tile). It should be executed when we are done with all the tiles so the call is inserted in the inner space iterator prologue (see the user model below).

The 2 basic kernels are first modeled.

Then the Matrix Max user kernel generator:

And here is the code that is generated by the auto-tiler after a call to MatrixMax("MatMax", 200, 300)

Basic kernels are written assuming all their data can fit into the shared level 1 memory. Usually a kernel function will access a data chunk through a pointer argument and will be informed about the data chunk characteristics by means of dimension arguments. A basic kernel manipulates a tile: one access pointer, one width argument and one height argument (a tile can also be of dimension 1). Scalar arguments, shared level 1 preloaded arguments, arguments accessed directly in level 2 can also be used by a basic kernel.

Basic kernels can be either sequential or parallel. A sequential kernel will run on a single core (core 0 of the cluster). For example, a sequential kernel can handle the configuration of the HWCE convolutional accelerator. A parallel kernel is meant to be run on all the available cores of the cluster. When it is called it is dispatched on all the active cores. Writing an optimized kernel usually involves dealing with vectorization to get as much as performance as possible from a single core and then dealing with parallelism to use as many cores in the cluster as possible.

Basic kernels define the functions manipulated by the GAP8 tile generator. Their interfaces (C data type template) as well as their calling nature (parallel versus sequential) are modeled.

The functions that the basic kernel models describe are called by the auto-tiler at runtime so should be in functions in source external to the model.

The following API is used to add a basic kernel model.

In this first example we show how to write a basic kernel performing a parallel addition between two 2D integer matrices with a fixed, bias offset.

The parallel addition will look like:

And this is how the function is modeled as a basic kernel:

The second example shows how to model a sequential function to switch on the HWCE accelerator.

In this case, this is a simple sequential call to a preexisting library function. The C function to switch on the HWCE is in the GAP8 run-time and is called HWCE_Enable()

This is the way this call is modeled.

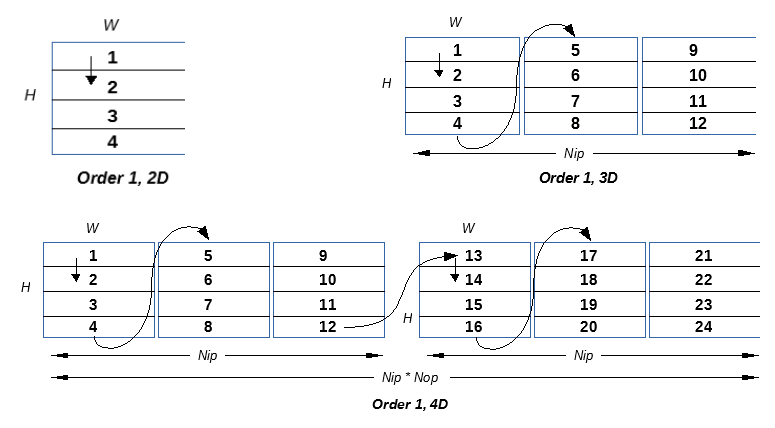

The iteration space of a user kernel can be of dimension 1, 2, 3, or 4.

The inner level of the iteration space is assumed to be 2D (with 1D as a special case where one of the inner dimensions is set to 1). The inner level is the one that will be tiled by GAP8 auto-tiler. In this document we refer to this inner level as a plane, either input or output.

***Note: A 2D input or output can be embedded into an iteration space whose dimension is greater than 2. In this case each 2D plane is consumed several times.***

Two different iteration orders are supported when dimension is greater or equal than 3:

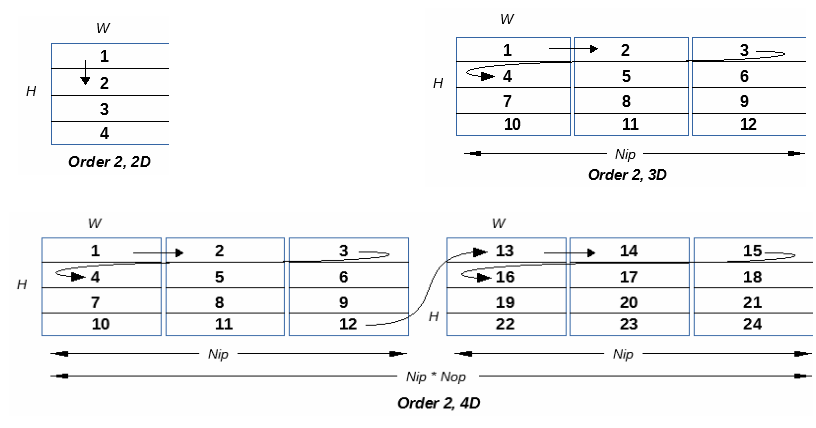

The diagrams Below illustrate how tiles are traversed as a function of the dimension of the iteration space in Order 1.

The diagrams Below illustrate how tiles are traversed as a function of the dimension of the iteration space in Order 2.

In the current implementation only order 2 is fully supported.

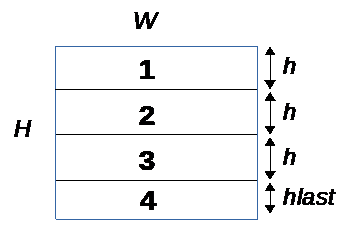

Tiles have 2 possible orientations:

***Horizontal:*** The [W x H] data plane is divided into N tiles of size [W x h] and one last tile of size [W x hlast] where hlast < h

***Vertical:*** The [W x H] data plane is divided into N tiles of size [w x H] and one last tile of size [wlast x H] where wlast < w

It is important to note that one of the 2 dimensions is left untouched so a single line or a single column must fit into the memory constraints given to GAP8 auto-tiler.

Deciding which orientation to choose is driven by the nature of the algorithm. For example, a function computing a bi-dimensional FFT on a 2D input plane of size [S x S] will execute in two passes. A first pass where a 1D FFT is applied on each line so the natural choice is horizontal. Then the second pass will apply a 1D FFT on each column of the 2D plane produced by the first pass, so vertical is the natural choice.

In the current implementation the orientation choice applies to all user kernel arguments. In future version this constraint will be removed to allow the developer to decide a different orientation for each kernel argument.

A user kernel is a collection of fields. The following library function is used to create a user kernel:

The following sections describe the content of each of the user kernel fields.

A string with the kernel name which must be unique.

Specifies the number of input planes (Nip), number of output planes (Nop), default width (W) and height (H) of a plane for the user kernel.

Note that Nip and Nop are shared by all kernel arguments while W and H can be redefined for each kernel argument.

The following library function is provided to capture the user kernel dimension info:

For example, MyFavoriteKernel below has 4 input planes, 4 output planes and a default data plane of 32 column and 28 lines:

The iteration order captures the overall structure of the user kernel. First the number of dimensions and then the way the iteration is traversed.

Dimensions: KER_DIM2, KER_DIM3, KER_DIM4

***Iteration Order 1***

KER_DIM2, KER_TILE

: 2D. Tiled inner data plane

KER_DIM3, KER_IN_PLANE, KER_TILE

: 3D. For each Nip in data planes all tiles in a plane, Nop is treated as equal to 1

KER_DIM3, KER_OUT_PLANE, KER_TILE

: 3D. For each Nop out data planes all tiles in a single input plane, Nip is treated as equal to 1

KER_DIM4, KER_OUT_PLANE, KER_IN_PLANE, KER_TILE

: 4D. For each Nop out data planes, for each Nip input data planes, for all tile in plane

***Iteration Order 2***

KER_DIM2, KER_TILE

: 2D. Tiled inner data plane

KER_DIM3, KER_TILE, KER_IN_PLANE

: 3D. For each tile of each Nip input planes, Nop is treated as equal to 1

KER_DIM3, KER_OUT_PLANE, KER_TILE

: 3D. For each Nop out data planes all tiles in a single input plane, Nip is treated as equal to 1

KER_DIM4, KER_OUT_PLANE, KER_TILE, KER_IN_PLANE

: 4D. For each Nop out data planes, for each tile in each Nip input data planes

This is the general iteration pattern for a user kernel, then each kernel argument can traverse the whole iteration space or only a subset. For example, a 2D kernel argument when embedded in a 4D user kernel will iterate Nip*Nop times on the same WxH data plane.

Note: currently only Iteration Order 2 is fully supported.

For example, MyFavoriteKernel below follows iteration Order 2: 4 dimensions, first out-planes then tiles then in-planes:

In a 2D data plane of dimension W x H, tiling can be performed horizontally or vertically. Currently this is a user kernel level parameter and all user kernel arguments are tiled in the same direction. In the future global orientation will be able to be overridden on a per argument basis.

When a 2D data plane is tiled, all the tiles except the last one will have the same size. This size is computed to gain maximum benefit from the configured memory budget.

Orientation can be: TILE_HOR or TILE_VER

For example MyFavoriteKernel below will tile the data plane horizontally.

A user kernel will end up as a C function after it has been processed by the auto tiler. For this reason, the C template of this function must be provided. This is like the template provided for a basic kernel, i.e. a list of C variable names and their associated C types.

The CArgs library function is used to do this. It takes two parameters. Firstly, the number of C arguments and secondly a list of parameters modeled as <Type Name, Arg Name> pairs, the TCArg function is used to create the pair.

For example MyFavoriteKernel below has 4 C arguments: In1, In2, Out and Bias with their respective C types.

You will note here that the dimension of the arguments is not passed, they will be captured in the kernel argument description part of the model if they are candidates for tiling. In case that they are pure C arguments, not candidates for tiling, then their dimensions should be passed.

The CCalls field indicates the link between the User Kernel and one or more Basic Kernels. It models the sequence, call position and argument bindings for Basic Kernels called from this user kernel.

The location of calls to basic kernels in the user kernel iteration sequence depends on the iteration order, Order 1 or Order 2.

Here are the locations where calls can be inserted as a function of iteration order:

The code fragments below show where the calls are inserted in relation to the two possible iteration orders:

***Iteration Order 1***

***Iteration Order 2***

At each insertion point, calls are inserted in the order they appear in the user kernel call sequence.

User kernel calls are captured by the following library call, the number of calls in the user kernel and then a list of basic kernels calls:

Each call is captured by:

Where CallName is a basic kernel name that must exist, CallLocation is a call location in the iteration template and BindingList is a list of bindings between basic kernel C formal arguments and different entities:

Each argument for each call can be bound to combination of user kernel arguments (tiles or attribute of tiles such as tile width and tile height), plain C arguments or immediate values.

The possible binding sources are listed below.

K_Arg(UserKernelArgName, KER_ARG_TILE)

: Pointer to a tile

K_Arg(UserKernelArgName, KER_ARG)

: Pointer to data plane

Apply to tiled kernel arguments.

K_Arg(UserKernelArgName, KER_ARG_TILE_W)

: Width of the current tile. Unsigned int.

K_Arg(UserKernelArgName, KER_ARG_TILE_W0)

: Default tile width, last tile can be smaller. Unsigned int.

K_Arg(UserKernelArgName, KER_ARG_TILE_H)

: Height of the current tile. Unsigned int

K_Arg(UserKernelArgName, KER_ARG_TILE_H0)

: Default tile height, last tile can be smaller

K_Arg(UserKernelArgName, KER_ARG_NTILES)

: Number of tiles in the data plane. Unsigned int.

K_Arg(UserKernelArgName, KER_ARG_TILEINDEX)

: Current tile index. Unsigned int.

K_Arg(UserKernelArgName, KER_ARG_TILEOFFSET)

: Current tile offset starting from the origin of the iteration sub space of this user kernel argument. Unsigned int.

C_Arg(UserKernelCArgName)

Subscripted by the current index of input plane, output plane or tile multiplied by a constant

C_ArgIndex(UserKernelCArgName, [Iterator], MultFactor)

: where [Iterator] is KER_IN_PLANE, KER_OUT_PLANE or KER_TILE. Note that the C kernel argument has to be a pointer for this binding to be legal

Imm(ImmediateIntegerValue)

Note: the binding list order has to follow the basic kernel argument list order.

For example MyFavoriteKernel below contains a single call to the library kernel MatrixAdd located in the inner loop

User kernel arguments are the inputs and outputs to the user kernel, the entities that will undergo tiling to allow them to fit into the available level 1 memory.

As you can see, each user kernel argument can have a different width and height. The GAP8 automatic tiler models the ratios between these different dimensions and tries to find out a tile size (potentially different for each user kernel argument) that will fit within the shared level 1 memory budget it has been given. Tiles can be subject to additional constraints:

All these constraints can be expressed in a user kernel argument.

To create a kernel argument, the following library call is used:

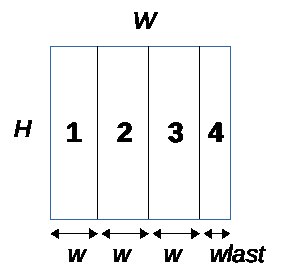

A user kernel argument object type is either a flag built from a set of basic user kernel argument properties or a pre-defined name.

***Names built as a flag from user kernel argument properties***

The set of pre-defined properties which can be OR'ed (|) together is:

O_IN, O_NIN : Is an input or not an input

O_OUT, O_NOUT : Is an output or not an output

O_BUFF, O_NBUFF : Is a buffer or not a buffer

O_TILED, O_NTILED : Is tiled or not. When not tiled, the whole data plane is accessible in shared level 1 memory. For example, a 2D convolution has one argument that is tiled (the input data) and another one that is not tiled (the coefficients)

O_ONETILE, O_NONETILE : A buffer property. When ONETILE is set, a buffer of dimension WxH will be given only the dimension of a tile whose size is proportional to the size of the tiles generated for the other kernel arguments.

O_DYNTILE, O_NDYNTILE : A buffer property. When O_DYNTILE, the height if tiling orientation is horizontal or the width if orientation is vertical, of the buffer will be adjusted to the number of tile computed by GAP8 auto-tiler. This is useful when a dynamic buffer is needed to implement a reduction phase after a result has been computed for each tile independently and final result must be obtained combining all these results into a single one. Usually the declared W or H is the one of another user kernel input and the auto-tiler adjusts it.

O_DB, O_NDB : Argument is double or triple buffered in L1 memory, or it is not multi-buffered

O_L2DB, O_NL2DB : Argument home location is an external memory and is double or triple buffered in level 2 memory, or it is not an external memory

O_3D, O_N3D : Argument has 3 dimensions or not

O_4D, O_N4D : Argument has 4 dimensions or not (note that a 4D argument is also a 3D one)

For example, O_IN|O_DB|O_L2DB|O_4D is an input pipelined in level 1 memory and in level 2 memory whose home location is external memory. Its dimension is 4.

***Pre-defined names***

The diagrams below summarize the set of pre-defined names.

For example OBJ_IN_DB_L2DB_4D is an input pipelined in level 1 and in level 2 memory whose home location is external memory. It's dimension is 4.

A pair of unsigned ints specifying the dimension of the data plane.

An unsigned int specifying the size in bytes of the data plane elementary data type.

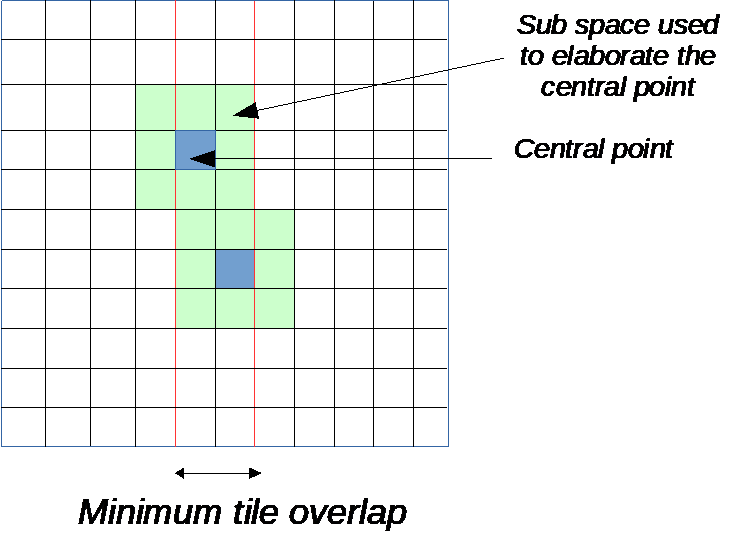

An unsigned int capturing the amount of overlap between two adjacent tiles. This is useful in case an output is computed as a function of a point in the input data plane and its neighborhood. If to compute an output you need inputs at a maximum distance K from the point of computation then 2 adjacent tiles should overlap by at least 2*K points.

Specifies a constraint on a property of the tile dimension that is calculated by the GAP8 auto-tiler. When tiling is horizontal the constraint is on the height of the tile, and when tiling is vertical the constraint is on the width of the tile. A constraint will be applied by the auto-tiler to all the tiles except the last one. If this is not possible the model cannot be tiled.

These are the possible constraints:

Specifies the developer's preference for the dimension of the tile that is calculated by the GAP8 auto-tiler. It is expressed as an unsigned int and when not zero the preferred dimension of the tile chosen is a multiple of this value.

Generally, a user kernel argument is connected to a C argument and in this case the name of this C argument should be provided. In the case where the user kernel argument is only internal to the user kernel or user kernel group then there is no binding and null (0) should be used.

Generally, the mechanism to move from one data plane to another one in the iteration space for user kernel arguments with dimensions strictly greater than 2 is inferred from the object type. In some cases, it can be desirable to give a better control on this update process. For example, the GAP8 hardware convolution engine can produce 3 full 3 x 3 convolution outputs. Here 3 adjacent output data planes are involved and therefore the move to next group of outputs should use a step of 3 * size and not 1 * size of the output plane as is the case for an implicit update.

Next plane update is expressed as a non 0 unsigned integer. If 0 then default rule is applied.

Back to our simple matrix addition example, a possible final version is shown below:

The first argument is an input coming from L2 memory and it is multi buffered in shared L1 memory so that performance is optimized. The basic plane is 75 x 75 of integers (4 bytes). It has 3 dimensions and since we have declared that we have 4 input planes in the KernelDimensions section we have 4 basic planes.

The second argument has the same characteristics than the first argument.

The third argument is an output that should go to level 2 memory and that is multi buffered in level 1 memory again to incur no performance penalty due to memory transfers. It has 3 dimensions and since we have declared that we have 4 output planes in the KernelDimensions section we have 4 basic planes.

The 3 user kernel arguments are tiled.

What this example does is to add in each output matrix the sum of all input matrices plus a scalar bias.

As you can see each matrix occupies 75 * 75 * 4 = 22.5 Kbytes. There are 4 of them for In1, 4 for In2 and 4 for Out so a total of 270Kbytes. Clearly this does not fit in the shared L1 memory. The GAP8 auto-tiler produces code that will transparently move sections of the 270Kbytes back and forth from L2 to shared L1 and make them available to the basic kernel function doing the actual calculation (our special matrix addition) making sure all the cores are always active.

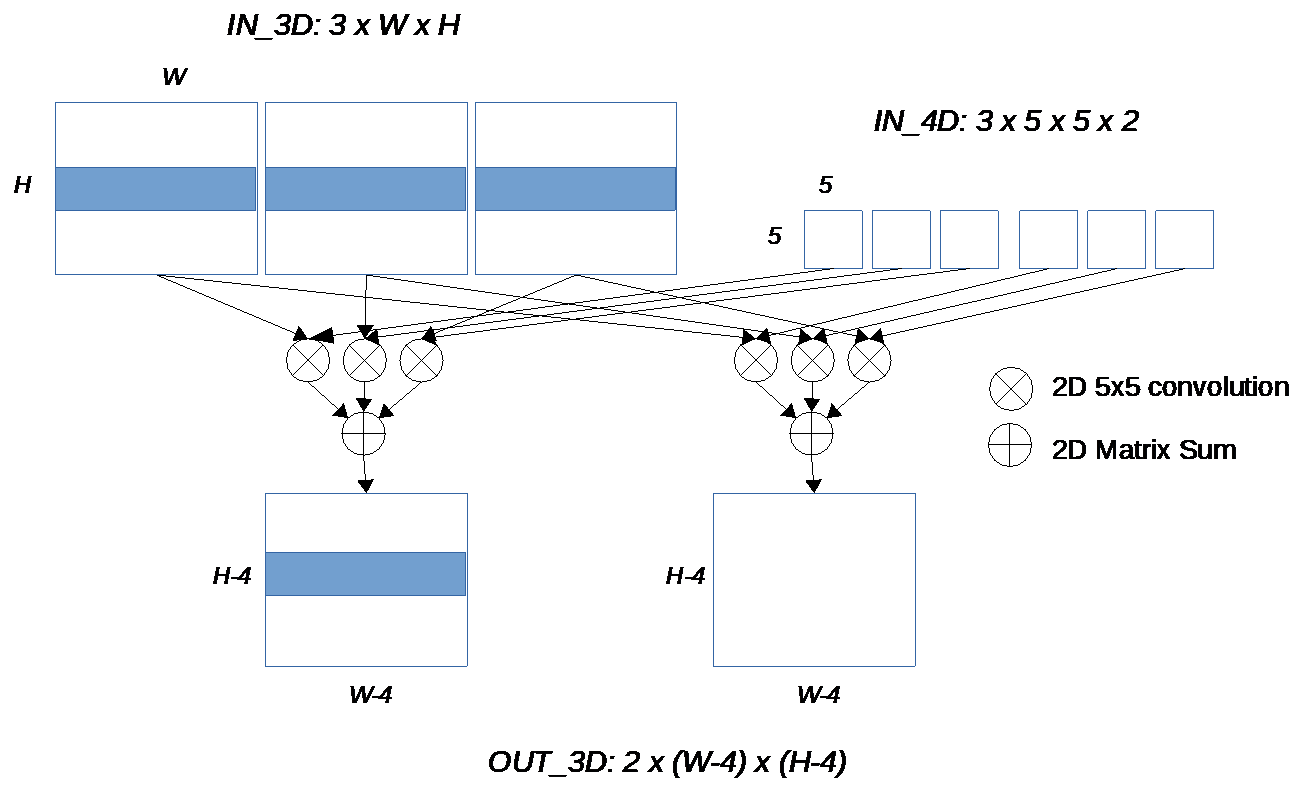

We assume 3 input data planes of size W x H and 2 output data planes of size W - 4 x H - 4 (padding is not performed). The diagram below gives a high-level view of what needs to be done.

Since to get the result, we must sum up the convolution results from all input planes, we can also assume that we start the summation with a matrix made up of identical values, a bias. Planes contain fixed point numbers made up of 16 bits (short int).

Instead of having a specialized implementation, we want to allow the number of input and output data planes to be specified so we simply embed the user kernel in a C function with proper arguments.

Our 2 basic kernels are KerSetInBias that copies the same constant value in a matrix and KerDirectConv5x5_fp that takes care of the convolution itself. The convolution takes a 2D input In, a set of filter coefficients (25 in this case) and produces a 2D output. It performs normalization shifting the result by Norm.

This example illustrates:

LOC_IN_PLANE_PROLOG. The convolution itself must be performed on every single tile so it is in the inner loop.K_Arg())C_Arg()) or as plane indexed (C_ArgIndex())It is useful to decompose a user kernel into a group of connected user kernels. User kernel groups allow this.

A user kernel group is described by a set of 2 anchors around a list of user kernel definitions. The first anchor marks the beginning of the user kernel group and defines its name. The second anchor closes the group. Then a second section models the C kernel template for the group and how the user kernels in the user kernel group should be connected together.

Here is the API to open and to close a kernel group:

To model a kernel group the API is:

As a reminder:

Instead of Call() which is used to model a call to a basic kernel, we use UserKernelCall(). Its interface is the same as Call() but it has some additional restrictions.

Some details on the user kernel group call sequence:

LOC_GROUP.The input is a 2D byte pixel image of dimension Dim x Dim. Dim has to be a power of 2.

We first have to expand the input image into I/Q pairs. I and Q are the imaginary and real parts of a complex number, both represented as Q15 fixed point numbers in a short int. We use the Image2Complex() basic kernel. Tiling is horizontal.

Then we compute the FFT of each line of the expanded input, all the FFTs are independent. Therefore they can be evaluated in parallel. We use either a radix 4 or radix 2 FFT decimated in frequency (inputs in natural order, output in bit reverse order).

Finally, we reorder the FFT outputs with SwapSamples_2D_Horizontal_Par.

These 3 steps can be grouped together into a single user kernel in charge of the horizontal FFTs.

Once horizontal FFTs have been computed, we have to compute a 1D FFT on each column of the horizontally transformed input, so we use vertical tiling. Since the vertical FFT is also decimated in frequency, we have to reorder the vertical FFTs output. These 2 basic kernels are grouped into a single user kernel in charge of the vertical FFTs.

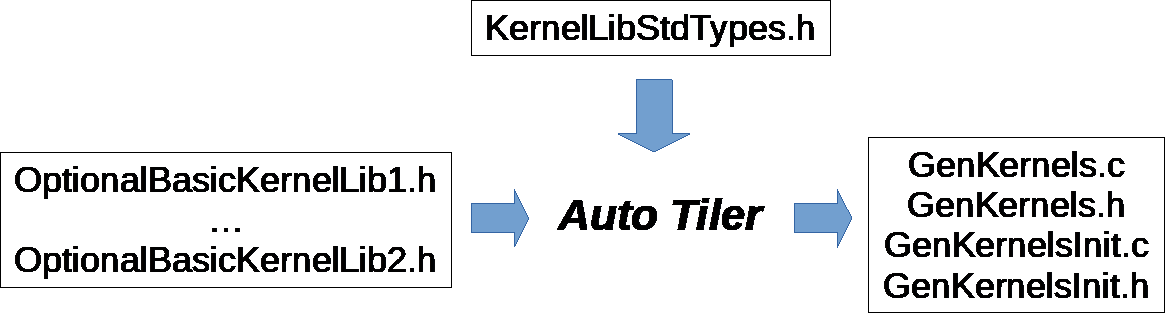

As already mentioned a model is just a C program. To get the generated code you need to compile and execute the model.

The model makes use of the GAP8 auto-tiler library calls for which a header file needs to be included and a library to be added to the link list. All interfaces and data types are declared in AutoTilerLib.h and the library itself is AutoTilerLib.a.

Below is a simple example of a complete generator using the auto-tiler, MyProgram.c:

To compile and use the sample:

And run MyGenerator to have the tiled user kernels generated:

The GAP8 auto-tiler uses and produces files, the general scheme is illustrated below:

OptionalBasicKernelLibn.h : This is where the C templates for the basic kernels are expected to be found for proper compilation of the generated code. Both the C templates as well as the struct typedefs for the basic kernel arguments are included. It can be empty.

KernelLibStdTypes.h : Contains some internal tiler argument types definitions. This is the default name but it can be redefined.

The API to redefine KernelLibStdTypes.h and to provide which basic kernel libraries to use is the following:

Four files are produced by the auto tiler

GenKernels.c : The generated code for all user kernels and groups in the model

GenKernels.h : Include file for the generated code

GenKernelsInit.c : Some variable definitions

GenKernelsInit.h : Include file for the initialization code

The names used here are the default names, they can be overridden using the following function:

Four other symbols are also manipulated by the auto tiler:

L1_Memory : One symbol, a pointer or an array, in which all the tiles generated by the tiler will be allocated in the shared L1 memory.

L2_Memory : One symbol, a pointer or an array, in which all the tiles generated by the tiler will be allocated in the L2 memory.

AllKernels : One symbol, an array, in which user kernel descriptor is stored. Descriptors are generated only when user kernels are not inlined.

AllKernelsArgs : One symbol, an array, in which user kernel arguments descriptors are stored, AllKernels will point into it. These descriptors are generated only when user kernels are not in-lined.

These 4 names are default names, they can changed with the following function:

By default these 4 symbols are managed as arrays, you can make them dynamic (pointers) in order to have the memory allocated and deallocated dynamically. The execution log of the auto tiler tells you the number of bytes to be allocated for each of them.